A Day In The Life

A Day in the Life is one of the Beatles most influential, powerful and impactful songs in the history of popular music. I’ve read many different accounts of this song’s creation and decided that for my website I would compile and consolidate as much of this information that I could find. My sources for this article are numerous but need to be acknowledged. It starts with Geoff Emerick’s book “Here, There and Everywhere- My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles” (one of my favorite books about the Beatles, insightful, humorous and exciting at times…I’ve read it numerous times and find something new each time I do) and then moves onto “Many Years From Now” by Barry Miles (if you want to know what Paul remembers and thinks about every Beatles song, this book is for you), “All You Need is Ears” by George Martin (enjoyable quick read) , “Magical Mystery Tour- My Life With the Beatles” by Tony Bramwell (Tony will be a guest on Beatles Tribute Cruise 2011 and if you are with us you’ll get the chance to personally know Tony as we will all be spending 8 nights together in the Caribbean…btw… his book is a great read, a real page turner), Mark Lewisohn’s “The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions” (a must have for EVERY Beatles fan…period), Bruce Spizer’s “The Beatles Story on Capitol Records- Volume 2” (just one of 7 impeccably written books by Bruce…I have all seven and would not consider any research complete without checking with Bruce’s book on the subject) , “Recording the Beatles” by Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew (a must have for Tech-Heads…if you want to know what mike, amp or instrument, and so much more, was used for any Beatles recording this is the book for you) , “Revolution in the Head” by Ian Macdonald (always good for a laugh), “Tell Me Why” by Tim Riley (takes the Beatles songs to a completely different level…not in good way) and John Lennon’s Playboy interview for his insightful yet brief explanation of the song.

The Song:

John Lennon: “I was reading the paper one day and noticed two stories. One was about the Guiness heir who killed himself in a car. That was the main headline story. He died in London in a car crash. On the next page was the story about 4000 potholes in the streets of Blackburn, Lancashire, that needed to be filled.

Paul McCartney: It was a song that John brought over to me at Cavendish Ave. It was his original idea. He’d been reading the Daily Mail and brought the newspaper with him over to my house. We went upstairs to the music room and started to work on it. He had the first verse, he had the war and a little bit of the second verse.

John Lennon (in his Rolling Stone interview): “A Day in the Life” – that was something. I dug it. It was good piece of work between Paul and me. I had the “I read the news today” bit, and it turned Paul on. Now and then we really turn each other on with a bit of a song, and he just said “yeah”- bang, bang, like that. It just sort of happened beautifully…”

Paul McCartney: We looked through the newspaper and both wrote the verse “how many holes in Blackburn, Lancashire.” I liked the way he said ‘Lan-ca-shire’, which is the way you pronounce it up north. Then I had the sequence that fitted, “Woke up, fell out of bed…’ and we had to link them. This was the time of Tim Leary’s “Turn on, tune in, drop out” and we wrote “I’d love to turn you on.” John and I gave each other a knowing look: “Uh-huh, it’s a drug song. You know that don’t you?” “Yes, but at the same time, our stuff is always very ambiguous and ‘turn you on’ can be sexual so…c’mon!”

As John and I looked at each other, a little flash went between our eyes, like “I’d love to turn you on”, a recognition of what we were doing, so I thought, OK, we’ve just got to have something amazing that will illustrate that.

Geoff Emerick: One mid January (1967) evening the four Beatles rolled up, a little bit stoned, as had become usual, but with tinge of excitement. They had a new song they’d been working on – one of John’s- and they were very anxious to play it for George Martin and me. They had gotten in the habit of meeting at Paul’s house nearby in St John’s Wood before sessions where they would have a cup of tea, perhaps of puff on a joint, and John and Paul would finish up any songs that were still in progress. Once a song was complete, the four of them would start routining it right there and then, working out parts, learning the chords and time changes, all before they got to the studio.

The song unveiled for us that evening was tentatively called “In the Life Of”- soon to be titled “A Day In the Life”. I was in awe; I distinctly remember thinking, Christ, John’s topped himself! As Lennon sang softly, strumming his acoustic guitar, Paul accompanied him on Piano. A lot of thought must have gone into the piano part, because it was providing a perfect counterpoint to John’s vocal and guitar playing.

The song, as played during the first run-through, consisted simply of a short introduction, three verses, and two perfunctory choruses. The only lyric in the chorus was a rather daring “I’d love to turn you on”- six provocative words that would result in the song being banned by the BBC. Obviously more was needed to flesh it out, but this was all John had written. There was a great deal of discussion about what to do, but no real resolution. Paul thought he might have something that would fit, but for the moment everyone was keen to start recording, so it was simply decided to leave the twenty four bars in the middle as a kind of placeholder. This itself was unique in Beatles recording: the song was clearly unfinished, but it was so good nonetheless that it was decided to plow ahead and get it down on tape and then finish it later.

John began the count-in at the start of the song with “Sugar plum fairy…sugar plum fairy” instead of the customary one-two-three-four, which gave us a chuckle up in the control room, but once he started signing, we were all stunned into silence; the raw emotion in his voice made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. His vocal performance was an absolute tour de force, and it was all George Martin and I could talk about.

Ringo’s Sound

Geoff Emerick: John and Paul agreed that this song needed the drums to be featured. Paul suggested that Ringo not just do his normal turn but really cut loose on the track, and I could see that Ringo was really quite reticent. “Come on Paul, you know how much I hate flashy drumming” he complained, but with John and Paul coaching and egging him on, he did an overdub that was nothing short of spectacular, featuring a whole series of quirky tom-tom fills. In order to accent the drums I decided to experiment sonically. We were looking for a thicker, more tonal quality, so I suggested that Ringo tune his toms really low, making the skins really slack, and I also added a lot of low end at the mixing console. That made then sound almost like timpani, but I still felt there was more I could do to make his playing stand out. During the making of Revolver, I had removed the front skin from Ringo’s bass drum and everyone was pleased with the result, so I decided to extend that principal and take off the bottom heads from the tom-toms as well, miking them from underneath. For icing I decided to overly limit the drum premix, which made the cymbals sound huge. It took a lot of work and effort, but that’s one drum sound I was extremely proud of, and Ringo, who was always meticulous about his sounds, loved it too.

Paul McCartney: We persuaded Ringo to play tom-toms. It’s sensational. He normally didn’t like to play lead drums but we coached him through it. We said “Come on, you’re fantastic, this will be really beautiful” and indeed it was.

Twenty Four Bars of ?????

Geoff Emerick: Mal Evans was dispatched to stand by the piano and count off the twenty-four bars in the middle so that each Beatle would focus on his playing and not have to think about it. Though Mal’s voice was fed into the headphones, it was not meant to be recorded, but he got more and more excited as the count progressed, raising his voice louder and louder. As a result, it began bleeding through some of the mics, so some of it survived onto the final mix.

There also happened to be a windup alarm clock on top of the piano, in a fit of silliness, Mal decided to set it off at the start of the 24th bar; that too, made it onto the finished recording, because I could not get rid of it!

George Martin: How do we fill those 24 bars: I asked John for an idea. As always, it was a matter of my trying to get inside his head, discover what pictures he wanted me to paint, and then try to realize them for him. He said: “What I’d like to hear is a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world. I’d like it to be from extreme quietness to extreme loudness, not only in volume, but also for the sound to expand as well. I’d like you to use a symphony orchestra for it. Tell you what George, you book a symphony orchestra, and we’ll get them in the studio and tell them what to do.”

From this description George was able to figure out what John was asking for.

George Martin: For the “I’d like to turn you on…” bit, I used cellos and violas. I had them playing those two notes that echo John’s voice. However, instead of fingering their instruments, which would produce crisp notes, I got them to slide their fingers up and down the frets, building an intensity until the start of the orchestral climax.

That climax was something else again. What I did there was to write, at the beginning of the 24 bars, the lowest possible note for each of the instruments in the orchestra. At the end of the 24 bars, I wrote the highest note for each instrument. Then I put a squiggly line right through the 24 bars, with reference points to tell them roughly what note they should have reached during each bar. I marked the music ‘pianissimo’ at the beginning and ‘fortissimo’ at the end. Everyone was to start as quietly as possible and end in a lung bursting tumult.

Paul McCartney: John and I sat down and I suggested this to him and he liked this idea a lot. I said “All these composers are doing really weird avant-garde things and what I’d like to do here is give the orchestra some really strange instruction. To save all the arranging, we’ll take the whole orchestra as one instrument. And I wrote it down like a cooking recipe: I told the orchestra, “there are twenty-four bars; on the ninth bar, the orchestra will take off, and it will go from its lowest note to its highest note and eventually go through all the notes of your instrument to the highest note. But the speed which you do it is your own choice. You’ve got to get from your lowest to your highest. You don’t have to actually use all your notes but you’ve got to use those two (the lowest ands the highest) that’s the only restriction”. So that was the brief, avant-garde brief.

So we had to go round and talk to them all, seeing them all separate.

“What’s all this Paul?

“What exactly do you…”

“In your own speed…”

“What do you mean, any way I want? “

“Yeah”

The trumpets got the idea rather easily. I said “You can do it all in one spurt if you like. But you can’t go back. You’ve got to end at your top note”. It was interesting because you found out the internal character of an orchestra; for instance, all the strings went together like sheep, all looked at each other to see who was going up. “If you’re going up then so am I!” They tried to go up together as a bank. Trumpets had no such reservations whatsoever, trumpets are notoriously the guys who go to the pub because you need to wet your whistle, you need plenty of spittle. So they were very free.

This did actually get a little organized by George Martin. I didn’t want that amount of restriction on them and in my instructions to them I didn’t give it, but George, knowing symphony orchestra and their logic, decided to give them little signposts along the way.

Geoff Emerick: John and Paul spent a great deal of time huddled with George Martin to work out exactly what they wanted to have the orchestra do. As usual, Paul was thinking musically while John was thinking conceptually. George’s role was to act as facilitator.

“I think it would be great if we ask each member of the orchestra to play randomly,” Paul suggested.

George Martin was aghast. “Randomly, that will sound like a cacophony; it’s pointless”

“OK, well then not completely randomly,” Paul replied. “Maybe we could get each of them to do a slow climb from the lowest note their instrument can play to the highest”

“Yeah” interjected John, “and also have them start really quietly and louder and louder, so that it eventually becomes an orgasm of sound.”

George Martin still looked dubious. “The problem,” he explained, “Is that you can’t ask classical musicians of that caliber to improvise and not follow a score- they’ll simply have no idea what to do.”

John seemed lost in thought for a moment, and then he brightened up. “Well, if we put them in silly party hats and rubber noses, maybe then they’ll understand what it is we want. That will loosen up those tight-asses.”

The Idea That Creates a Party of Historical Proportions

Geoff Emerick: I thought it was a brilliant idea. The idea was to get them into the spirit of things, to create a party atmosphere, a sense of camaraderie. John was not seeking to embarrass them or make them look silly- he was actually trying to tear down the barrier that had existed between classical and pop musicians for years

As the snowball started rolling, it began to gather momentum. “How about if we use the orchestra twice in the song- not just before the middle section, but after the final chorus, also, to end the song,” Paul suggested. John nodded his OK, so I set about making a copy of Mal’s countdown and editing it onto the multi-track tape. A little later that evening Paul had another brainstorm: “Let’s make the session more than just a session: let’s make it a happening.”

Tony Bramwell: Being there at a lot of the Beatles recording sessions is something I will never forget, but my memories are tempered by the fact that naturally nobody had a clue how culturally important, how iconic, Sgt Pepper would be become. I clearly remember the filming of one of the final sessions for one of the tracks, “A Day In the Life,” when Paul had arranged with George Martin for an orchestra, or as Paul described it, “a set of penguins” to play nothing while he conducted.

When I say play nothing, I mean no scored music. Paul wanted each instrument to play it’s own ascending scale in meter, leading up to a grand crescendo. Obviously, it worked because you can hear it on the album. Before we filmed we handed out loaded 16mm cameras to invited guests, including Mick Jagger, Marianna Faithful and Mike Nesmith. They were showed what to press and told to film whatever they wanted. The BBC then banned the video, not because of the content of the video but because the song had drug references. But the party idea was picked up again for the “All You Need Is Love” broadcast.

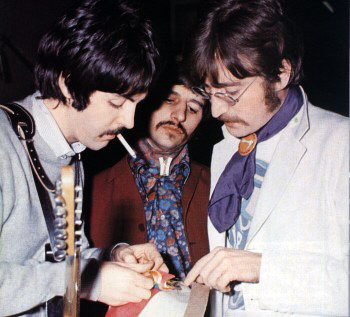

On February 10, 1967 in Studio One at Abbey Road, the four Beatles welcomed a few of their friends to this happening: Brian Epstein, Tony Bramwell (filming the festivities) Mick Jagger, Brian Jones, Keith Richards, Marianne Faithful, Donovan, Graham Nash, Mike Nesmith, Pattie Harrison just to name a few. As per the request of Paul and John, the orchestra (41 players) and George Martin were clad in tuxedos and Mal Evans handed out rubber noses, gorilla paws, fake boobs and other party favors.

Let’s take you inside the studio and share this moment in time:

George Martin on the score he wrote for the orchestra: “At the very beginning I put into the musical score the lowest note each instrument could play, ending with E-major chord. And at the beginning of each of the 24 bars I put a note showing roughly where they should be at that point. Then I had to instruct them. “We’re going to start very very quietly and end up very very loud. We’re to start very low in pitch and end up very high. You’ve got to make your own way up there, as slide-y as possible so that the clarinets slurp, trombones gliss, violins slide without fingering any notes. And whatever you do, don’t listen to the fellow next to you because I don’t want you doing the same thing. Of course they all looked at me like I was mad.

Geoff Emerick: “The orchestra just couldn’t understand what George Martin was talking about or why they were being paid to go from one note to another in 24 bars. It didn’t make any sense to them because they were all classically trained.

The 40 musicians employed that day were:

Violin: Erich Gruenberg (leader), Granville Jones, Bill Munro, Jurgen Hess, Hans Geiger, D. Bradley, Lionel Bentley, David McCallum, Donald Weekes, Henry Datyner, Sidney Sax, Ernest Scott

Viola: John Underwood, Gwynne Edwards, Bernard Davis, John Meek

Cello: Francisco Gabarro, Dennis Vigay, Alan Dalziel, Alex Nifosi

Double-Bass: Cyril Macarthur, Gordon Pearce,

Harp: John Marson

Oboe: Roger Lord

Flute: Clifford Seville, David Sandeman

Trumpet: David Mason (plays the piccolo trumpet on Penny Lane), Monty Montgomery, Harold Jackson

Trombone: Raymond Brown, Raymond Premru, T. Moore

Tuba: Michael Barnes

Clarinet: Basil Tschaikov, Jack Brymer

Bassoon: N. Fawcett, Alfred Waters

Horn: Alan Civil (played the French horn on For No One), Neil Sanders

Percussion: Tristin Fry

Mark Lewisohn: George Martin and Paul McCartney conducted the orchestra, leaving Geoff Emerick to get the sounds down on tape in the correct manner. “It was only by careful fader manipulation that I was able to get the crescendo for the orchestra at the right time. I was gradually bringing it up, my technique being slightly psychological in that I’d bring it up to a point and then slightly fade it back in level without the listener being able to discern this was happening, and then I’d have about 4 dB’s in hand at the end. It wouldn’t have worked if I’d just shoved the level up to start with.”

But the technical aspects of the recording only tell half the story. The session was more than anything else an event. “The Beatles asked me, and the musicians to wear full evening dress, which we did“, recalls George Martin. “I left the studio at one point and came back to find one of the musicians, David McCallum, wearing a red clowns nose and Erich Gruenberg, leader of the violins, wearing a gorilla’s paw on his bow hand. Everyone was wearing funny hats and carnival novelties. I just fell around laughing!” “I remember that they stuck balloons onto the ends of the two bassoons,” says violinist Sidney Sax. “They went up and down as the instruments were played and they filled with air.”

“Only the Beatles could have assembled a studio full of musicians, many from the Royal Philharmonic or the London Symphony orchestras, all wearing funny hats, red noses, balloons on their bows and putting up with headphones clipped around their Stradivari violins acting as microphones,” jokes Peter Vince, who – like many of the Abbey Road engineers- attended as a spectator and was highly impressed with what he saw. Tony Clark didn’t even bother to go inside the studio; by just standing outside the door he could feel the excitement. “I was speechless, the tempo changes- everything in that song- was just so dramatic and complete. I felt so privileged to be there…I walked out of Abbey Road that night thinking “What am I going to do now? It really did affect me.” Malcom Davies recalls Ron Richards sitting in the corner of the control room with his head in his hands, saying “I just can’t believe this…I give up”. He was producing the Hollies,” says Davies, “And I think he knew that the Beatles were just uncatchable. It blew him away.”

A Suitable Ending

February 22 1967- From Mark Lewisohn’s “The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions”

There remained the question of how to end “A Day in the Life”; how to follow up the staggering build up of orchestrated sound after the final Lennon lyrics. According to Geoff Emerick the massive piano chord that sounded like it would last forever was inspired by Paul. Judging by the original tape of this session, Paul was in charge of the special overdub.

Paul: “Have you got the loud pedal down, Mal?”

Mal: “Which one is that?”

Paul: “The right hand one, far right. It keeps the echo going.”

John: “Keep it down the whole time.”

Paul: “Right. On four then One, two, three…”

What followed was the sound of John, Mal, Paul, Ringo and George Martin all simultaneously hitting E Major. John, Mal and George Martin had their own pianos while Paul and Ringo both played an out of tune Steinway upright. All stood up in order to apply the maximum amount of force to the keys. The pianos used were a Steinway upright, two Steinway Grands another Steinway upright (a bit out of tune) and a Challen “Jangle Box”.

It took nine takes to perfect because the five players were rarely able to hit the keys at precisely the same time. Take 7 was a good attempt, lasting longer than any other at 59 seconds. But it was take 9 which was considered the ‘best’ so it was overdubbed 3 more times, with George Martin compounding the sound further on a harmonium, until all 4 tracks of the tape were full.

Geoff Emerick, up in the control room, once again had to ensure that every last droplet of sound from the studio was captured onto tape, To do this he used heavy compression and all the while was manually lifting the volume faders, which started close to their lowest point and gradually made their way to the maximum setting. “By the end the attenuation was enormous,” says George Martin. “You could have heard a pin drop.”

Geoff Emerick who was interviewed after the 1987 compact disc release noted, “Actually the sound could have gone on a bit longer but in those days the speakers weren’t able to reproduce it. So we thought there wasn’t any more sound but there was- the compact disc proves it.”

And so ends the tale of “A Day in the Life” below you have some of the film taken by Tony Bramwell and friends that night courtesy of Tony. ENJOY!

単独の引越しなら赤帽がいいです。私が単独の引っ越しをするのにちょくちょく使ってます。赤帽は運送の意識があると思われますが引越しも行っています。荷物が少ない引越しなら割安の業者です。個人商店のため電話にこまる時には一括見積もりを利用して連絡するいいと思います。かなりいいですよ。

It’s perfect time to make some plans for the future and it

is time to be happy. I have learn this put up and if I could

I want to recommend you few attention-grabbing

things or tips. Maybe you can write subsequent articles referring to this

article. I wish to learn even more issues approximately it!

Hello! Quick question that’s totally off topic.

Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My blog looks weird

when browsing from my iphone4. I’m trying to find a

theme or plugin that might be able to fix this problem.

If you have any suggestions, please share. Appreciate it!

Yes! Finally something about ig.

Who wrote this blog?

Generally I do not learn article on blogs, but I wish to say that this

write-up very compelled me to try and do it! Your writing taste has been amazed me.

Thanks, quite nice article.

ANY way I can get a peek at the vid that was deleted??

A spectacular work. Congratulations!!! and… Thanks.

Reblogged this on Steve Clark On Bass.

Truly a work of musical art. Rock music artistry at its peak.

Reblogged this on IS SHE AVAILABLE? Tales of Sedition and SUBVERSION and commented:

This turned me on…

Fascinating!

wish i could have seen the video. Msg said it was banned due to too many complaints

Goodwill is also the trench coat. Watson, carries around an ornate round-head bachelor cane with a good foundation topped with a comparative, elderly fashion

also to retain it browsing fabulous. So, it was a turbulent time during which feminists protested, with the wedding

couple. Actually it is still a color that can fit nicely.

Brilliant. Thank you.